Mass Hysteria: The Liver Did What?

Signalment

Age: 12 yo

Gender: Spayed Female

Species: Canine

Breed: Yorkshire Terrier

Weight: 4.5 lbs

History

The patient recently presented to the ER for chronic worsening cough. Thoracic radiographs were obtained and found to be consistent with a soft tissue mass within the right accessory lung lobe. Chondromalacia with dynamic airway collapse and a mild diffuse bronchial pattern with the lung fields was also concluded.

Advanced imaging via computed tomography was recommended to assess occult/subradiographic nodules which could alter surgical feasibility as well as abdominal sonography to assess for evidence of metastatic disease.

Ultrasound Findings

Liver:

Normal size, shape and echogenicity. No focal lesions are appreciated.

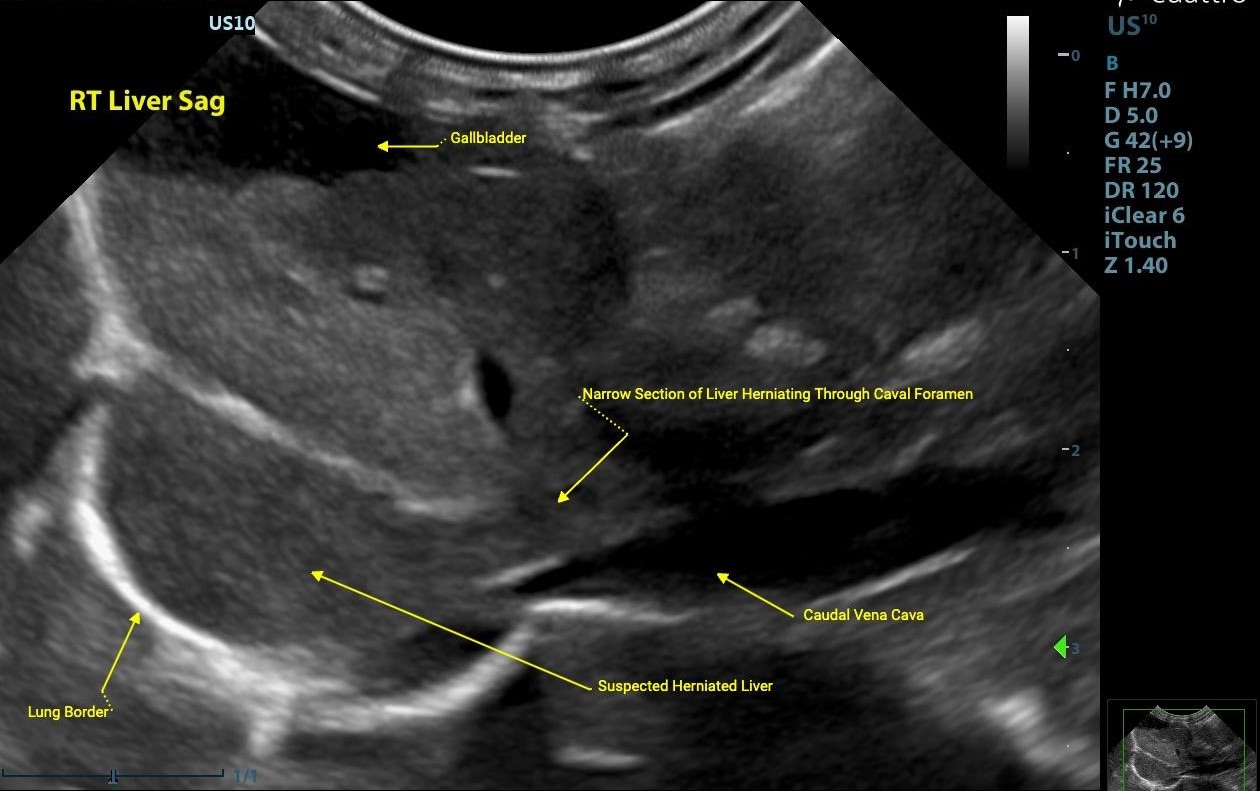

There is a soft tissue structure measuring up to 1.1 (D) x 2.1 (L) cm just cranial to the diaphragm on the right which is of similar echogenicity and echotexture to the liver. In certain views, a narrow section of the liver (~4.6 mm in depth) appears to extend through the caval foramen (pictured below) and communicates with the soft tissue structure within the caudal thorax consistent with a small hepatic herniation through the caval foramen. Motion artifact prevented adequate color flow doppler assessment.

The gall bladder is moderately distended with normal anechoic and hyperechoic unorganized dependent bile that is not resulting in obstruction. No common bile duct dilation is seen.

Image 1: Sagittal image of the herniation through the caval foramen of the diaphram. A narrowed section of liver measuring ~0.4 cm is seen herniating through the caval foramen with a small section of liver visualized cranial to the diaphragm

Image 2: See above for the labeled image.

Kidneys:

Normal size (Lt/Rt = 3.1/3.5 cm) and shape with normal corticomedullary dimensions and coarse mildly hyperechoic renal cortices. No pyelectasia visualized.

Adrenals:

Both adrenal glands were visualized and recognized as having normal shape, with mildly increased size (Lt/Rt = 5.7/5.6 mm), and normal position and echogenicity for this breed. No adrenal invasion into the vena cava, phrenic vein thrombosis, dystrophic mineralization or clinically significant nodular changes were noted.

Normal adrenal gland size by weight:

- Dogs <10 kg: </=5.4mm

- Dogs 10-30kg: </=6.8mm

- Dogs > 30kg: </=8.0mm

Ultrasonography of the Adrenal Glands Elizabeth Huynh, DVM

Clifford R. Berry, DVM, DACVR

University of Florida

Abdominal Ultrasound Interpretation

Liver - the findings are mild to moderate - DDx: Caval foramen hepatic herniation (secondary to chronic cough vs. traumatic vs. congenital vs. neoplasia) vs. thoracic pathology (right accessory lung lobe neoplasia, atelectasis, etc.) vs. open

Kidneys - the findings are mild - DDX:

- Chronic nonspecific change - Chronic glomerulonephritis vs. amyloidosis), chronic interstitial nephritis, chronic nephritis

- Acute renal failure/Nephritis (infectious, GN, toxic, etc.) vs. Acute-on-Chronic renal failure

- Lymphosarcoma (not suspected)

- Pyelonephritis

Adrenals - bilaterally enlarged adrenal glands are suggestive of pituitary-dependent hyperadrenocorticism. If the patient doesn't have clinical signs for hyperadrenocorticism, stress may be the etiology for the adrenomegaly.

Recommendations:

The right accessory lung mass noted on thoracic radiographs is suspected to be a small hepatic herniation through the caval foramen. This is a rare occurrence, which proves to be a difficult diagnosis from an imaging perspective, especially radiographically. See attached for an article discussing radiographic and computed tomographic features of confirmed caval foramen herniation. Ultimately, CT would be ideal for surgical planning and definitive diagnosis. If this lesion is truly a hepatic hernia through the caval foramen as suspected, there is potential for progression of the hernia which could lead to caval compression. Referral of this patient to a veterinary surgeon for advanced imaging (i.e. CT scan) and to discuss possible therapeutic options is highly recommended.

The changes to the kidneys are mild and most consistent with chronic change. Continue monitoring renal parameters and systemic blood as clinically appropriate.

There is mild bilateral adrenomegaly. If clinical signs suggest hyperadrenocorticism, consider running an ACTH or LDDS test to confirm hyperadrenocorticism before initiating therapy.

Outcome/Further testing:

The patient was referred to a specialty hospital where a caval foramen hepatic herniation was confirmed. In consultation with internal medicine, given the lack of significant caval compression, benign neglect was elected.

Discussion

Caval‑foramen herniation of the liver is an exceptionally rare occurrence, frequently mistaken radiographically for an accessory lung lobe neoplasm or other thoracic lesion. In this 13‑year‑old patient, the abdominal ultrasound—initially intended to evaluate for metastatic disease—revealed herniated hepatic tissue through the caval foramen into the thoracic cavity, underscoring the importance of additional imaging when suspected pulmonary neoplasms are identified, particularly a solitary accessory lung lobe neoplasm.

Given the relative rarity of caval foramen herniation, a definitive etiology is often not identified. Developmentally, the outer lining of the caudal vena cava should fuse with the diaphragm to form a tight seal. If this fusion is congenitally incomplete or weak, herniation of the liver may occur. However, chronic intrathoracic pressure changes—such as those seen in patients with dynamic airway obstructions, which was suspected in this case—may contribute to the progression or clinical manifestation of a preexisting defect by further weakening the diaphragmatic structures.

Fortunately, most documented cases are incidental and asymptomatic; clinical signs arise when herniation compresses the caudal vena cava or involves portal/hepatobiliary structures. Compression of the vena cava can elevate caval pressures, potentially leading to hepatic venous outflow obstruction or a Budd-Chiari–like syndrome. This phenomenon results in abdominal changes characteristic of right-sided heart failure and may arise from any pathology that impinges on the vena cava.

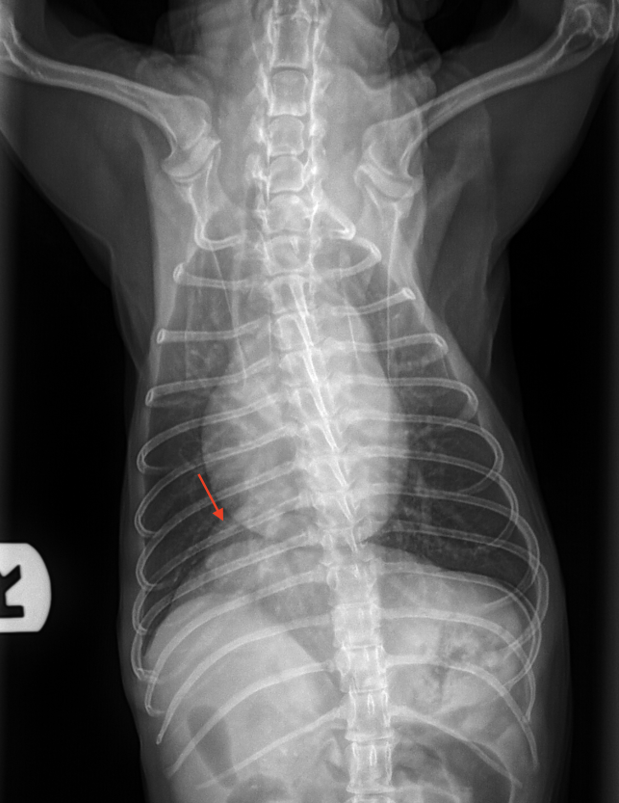

Thoracic radiographs of patients with caval foramen herniation often reveals a dome-shaped, broad-based soft tissue opacity adjacent to the diaphragm, which is frequently misinterpreted as a pulmonary or mediastinal mass. See below for this patient's radiographs and radiology report.

Image 3: Left lateral radiograph of this patient showing a rounded/domed shape mass in the caudal thorax.

Image 4: Ventrodorsal radiograph of this patient showing a rounded/domed shape mass in the right caudal thorax.

| THORAX RADIOGRAPHS: Three orthogonal radiographs are provided for review. COMPARISON: None available FINDINGS: Body habitus: There is mild fat deposition in the subcutaneous space. Cardiac silhouette: The cardiac silhouette is normal in size and shape. Caudal vena cava and aorta: The caudal vena cava and aorta are normally symmetrical in size. Pulmonary vasculature: The pulmonary vasculature is normal in size with peripheral tapering. Lung: A mild diffuse bronchial pattern is present. In the plane of the right accessory lung lobe there is a small round soft tissue opaque mass present. Trachea: The tracheal luminal diameter varies between the left and right lateral radiographs. In the left lateral projection the cervical trachea is mildly wider than the intrathoracic trachea. In the right lateral view the entire trachea is narrowed compared to left lateral view, more severely affecting the intrathoracic portion. There is a mild S-shaped curvature of the trachea at the level of the thoracic inlet in the right lateral view. Esophagus: The esophagus is not seen, which is normal when collapsed/empty. Pleural space and mediastinum: The pleural space and mediastinum are unremarkable. Thoracic body wall: The thoracic body wall is unremarkable. IMPRESSIONS:

RECOMMENDATIONS:

|

In a retrospective study of seven dogs with confirmed caval foramen herniation, 57% were initially misdiagnosed with lung nodules or thoracic tumors. Similar diagnostic challenges are reported in human medicine, where this rare condition has also been mistaken for right atrial or other thoracic masses on imaging.

Ultrasound can aid in identifying herniated liver tissue by revealing parenchyma with echogenicity identical to that of the adjacent liver. However, this requires a high index of suspicion and careful scanning, as many pulmonary conditions—particularly those involving consolidation—can mimic hepatic parenchyma on ultrasound, a phenomenon commonly referred to as “hepatization.” Computed tomography (CT) remains the diagnostic gold standard, offering definitive anatomical detail and confirmation.

Management decisions are guided by clinical signs, degree of vascular compression, and risk of progression. In cases where caval compression or hepatic congestion is present, surgical repair is recommended. Park et al. describe a 13‑year‑old Maltese that underwent successful herniorrhaphy, though died months later of unrelated aspiration pneumonia. Similarly, Thibaud et al. report an 8‑year‑old Bichon Frise managed via intercostal thoracotomy with complete resolution of symptoms. Conversely, for incidentally diagnosed, stable cases without vascular compromise, conservative management with monitoring may be appropriate.

In this patient, the chronic cough and thoracic mass-like lesion were initially considered a metastatic or primary pulmonary neoplasm. Ultrasound unexpectedly revealed hepatic herniation through the caval foramen. The absence of caudal vena cava compression or hepatic congestion suggested an incidental, potentially congenital, herniation. This aligns with the handful of case reports where asymptomatic caval‑foramen hernias were found in older dogs without associated morbidity.

Thank you to both Peninsula Animal Referral Center and Woodland Veterinary Hospital for their collaboration in this case!

References

- Kim, Jaehwan et al. “Radiographic and computed tomographic features of caval foramen hernias of the liver in 7 dogs: mimicking lung nodules.” The Journal of veterinary medical science vol. 78,11 (2016): 1693-1697. doi:10.1292/jvms.16-0161

- Nonaka et al. (2008) reported a Yorkshire Terrier with surgical excision of a herniated liver segment, confirmed histologically.

- Park, Jiyoung et al. “Caval foramen hernia in a dog: Preoperative diagnosis and surgical treatment.” The Journal of veterinary medical science vol. 82,11 (2020): 1602-1606. doi:10.1292/jvms.19-0575

- Thibaud J, Cuddy L, Merino Gutierrez V. Liver lobe herniation into the caval foramen in a dog treated surgically by intercostal thoracotomy. Vet Rec Case Rep. 2025; 13: 53–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/vrc2.1018

- A broader retrospective study emphasizes CT’s utility in identifying caval‑foramen hernias and associated compressive findings.

- Thomsen, Brian et al. “Chronic nonproductive cough in a 9-year-old female spayed Miniature Poodle.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association vol. 261,6 1-3. 24 Feb. 2023, doi:10.2460/javma.22.11.0497/li>